| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|

|

|||

Overview

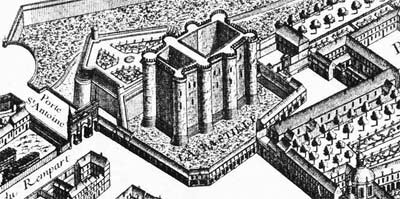

The Bastille, Porte and Faubourg St. Antoine, ca. 16th-17th cent. (click on image for expanded view of neighborhood) The Bastille {bah-steel'} was a prison in Paris, known formally as Bastille Saint-Antoine — Number 232, rue Saint-Antoine. The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789 marked the beginning of the French Revolution. The event was commemorated one year later by the Fête de la Fédération. The French national holiday, celebrated annually on July 14, is officially called the Fête Nationale, and commemorates the Fête de la Fédération — but it is commonly known in English as Bastille Day. Bastille (from bastide) is a French word meaning "castle" or "stronghold". In most accounts of French revolutionary history, La Bastille generally refers to the prison in Paris. Early HistoryThe Bastille (little bastion), originally called the Chastel Saint-Antoine, was built between 1370 and 1383 (under kings Charles V and Charles VI) to serve as a fortress for the protection of the city against Anglo-Burgundian forces during the Hundred Years' War. The four-and-a-half-story building, surrounded by its own moat, was located at the eastern main entrance to medieval Paris — overlooking the Faubourg St. Antoine of the Marais quarter, a former swamp. It had eight closely-spaced towers, roughly 77.1 ft. (23.5m) high, which surrounded two courtyards and the armoury. The towers were named as follows:

The outer stone walls, 15 feet (4.5m) thick at the base, were pierced with narrow slits by which the cells were lighted. In early times, the Bastille had entrances on three sides, but after 1580 only one, with a drawbridge over the moat on the side toward the river, which led to outer courts and a second drawbridge, and wound by a defended passage to an outer entrance opposite the Rue des Tournelles. Close beside the Bastille, to the north, rose the Porte Saint-Antoine — approached over the city fossé (ditch) by its own bridge. At the outer end of this bridge was a triumphal arch, built upon the return of Henri II from Poland in 1573. Both the gate and arch were restored for the triumphal entry of Louis XIV in 1667, but the gate (where Etienne Marcel was killed on July 31, 1358), was pulled down in 1674. Until the 17th century, the fort was used both as a castle and for the safekeeping of the royal treasure. During the first half of the 17th century, the Cardinal Richelieu (under King Louis XIII) converted the royal fortress into a state prison for the upper class — mainly people who committed high treason or some other kind of offense against either the King or the state (which were considered to be essentially the same). In addition to political prisoners, the Bastille also housed religious prisoners, writers of "seditious" and overtly sexual material, and young rakes held at the request of their families.

A lettre de cachet, signed by Louis XIV. (Musée Carnavalet, Paris) "Monsieur de Jumilhac, mon intention étant que le nommé Hugonet soit conduit en mon château de la Bastille, je vous écris cette lettre pour vous dire que vous ayez à l'y recevoir lorsqu'il y sera amené et à l'y garder et retenir jusqu'à nouvel ordre de ma part. La présente n'étant à d'autre fin, je prie Dieu qu'il vous ait, Monsieur de Jumilhac, en sa sainte garde. Ecrit à Versailles, le treize janvier 1765, Louis" The very often arbitrary warrant of arrest (known as the lettre de cachet, or letter with the royal seal) made the Bastille fortress one of the darkest symbols of royal despotism, although the conditions of imprisonment were generally quite comfortable. The prisoners could welcome visitors, bring their servants, their furniture, clothes, and books, and the daily ration paid by the state provided them a luxury cuisine. During the reign of Louis XV (1715-1774), the Bastille accommodated more and more ordinary criminals, whose existence there was rather less comfortable. Common prisoners were held within the five- to seven-story towers, each having a room around 4.6 m (15 feet) across and containing various articles of furniture. Thankfully, though, the infamous cachots — the oozing, vermin-infested subterranean cells — were no longer in use by the later half of the 18th century.

Voltaire

Count Alessandro di Cagliostro As the protectors of the Catholic religion, the king's authorities also imprisoned Protestants and freethinkers, and Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet) was arrested twice during his youth. In the last decades after 1750, many inmates were committed by their own families as insane or because of some shameful carnal deviation. Among the more prominent convicts of the late 1780s were Jean Henri Latude, a notorious and querulous swindler who was recaptured after escaping from prison on three separate occasions; the quack and alchemist Count Cagliostro; the diplomat and general Charles-François Dumouriez, later to be the hero of the French victory in 1792 at Valmy, but finally in 1793 deserting to the Austrian army; the wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, who was arrested for his own protection after the riots in the Faubourg St. Antoine in April 1789, when the rumour that he intended to cut his workers' salaries claimed more than 300 lives; and the Marquis de Sade, who however was transferred to the lunatic institution at Charenton on July 4, 1789, after he screeched out from the window of his cell to the neighborhood that "the prisoners were massacred and one should come to help". By this time, the government was already planning to close down and demolish the expensive medieval fortress. Although it is theorized by some that these utterances by the Marquis de Sade may have inspired the storming of the Bastille ten days later, in fact a far more complex series of events led to the violent insurrection. Interestingly, Count Alessandro di Cagliostro had been imprisoned in the Bastille because of his purported connection with a royal scandal known as the Affair of the (Diamond) Necklace, a charge for which he was ultimately acquitted. However, since the scandal indirectly involved Marie Antoinette, the wife of King Louis XVI, it is considered by historians to have been one of the precipitating factors in the French Revolution. Related VideosParis exhibit examines history of Bastille Prison (PressTV)Related videos: (replay) | Tour de la Liberté GO TO NEXT PAGE » A Prisoner's Account |

|||||

|

||||||||||